Maritime Heritage Trail

Welcome to a tour through the maritime heritage of the Sister Islands!

Welcome to a tour through the maritime heritage of the Cayman Islands! The three islands – Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac, and Little Cayman – are actually the tips of submerged mountains that protrude above the waters of the Caribbean Sea. Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, the two Sister Islands, were first sighted by Europeans in 1503, when Christopher Columbus’s two remaining caravels passed by them during the explorer’s fourth and final voyage to the New World. Since that time the Islands have been noted as both landmarks and navigational hazards, and as convenient places for historic mariners to stop for fresh water and to harvest sea turtles for fresh meat. First called Las Tortugas (The Turtles) for the great number of sea turtles in the waters surrounding them, the islands were later named Las Caymanas after the now-extinct caymans, or crocodiles, that used to abound on the beaches. Throughout their history, Caymanians’ lives have been tied to the sea: until fairly recently in maritime industries including turtling, shipbuilding, ropemaking, and shipping, and today through sailing, catboat racing, and both recreational and commercial fishing. Tourism, through watersports and cruiseship arrivals, maintains the strong link to the sea.

The Cayman Islands Maritime Heritage Trail was created to increase protection and appreciation for the Islands’ maritime heritage sites while providing enjoyment and education for the public. The Trail consists of a driving route around all three islands with stops marked by roadside signs. The Trail stops are presented in pictures and narratives on two poster/brochures, one for Grand Cayman and one for the Sister Islands. Some of the sites have been interpreted by organisations such as the National Trust and the Sister Islands Nature Tourism Project; these are marked with an asterisk (*) in the brochures. Look for interpretive signs, usually fairly near the Trail signs. Trail stops may be visited in any order to learn about the unique culture of our Islands. Please treat our Trail with care and respect by taking only pictures and leaving only footprints! The Maritime Heritage Trail is designed primarily as a driving route; visitors who choose to explore the sites on foot do so at their own risk. All shipwreck sites are protected under Cayman Islands law; violators will be prosecuted.

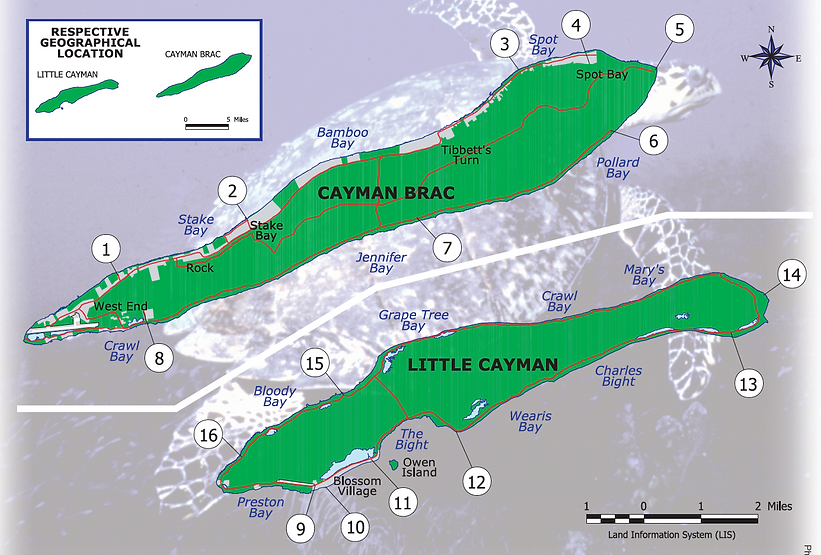

The Sister Islands of Cayman Brac and Little Cayman lie approximately 90 miles northeast of Grand Cayman. Their relatively remote location helps to preserve Caymanian culture and lifeways. With little arable land, residents traditionally depended on the sea for the necessities of life. The islanders made the most of their maritime lifeline, and Sister Islands’ mariners became world-renowned for their sailing and shipbuilding skills and seamanship. Unique heritage sites and natural resources are interpreted in Nature Tourism trails around both islands.

Cayman Brac, most northeasterly of the Cayman Islands, is 12 miles long and one mile wide. The Brac is distinctive for its limestone bluff (‘brac’ means bluff in Gaelic), which rises from sea level on the west end to 140 feet above the sea on the east end. The island supports a close-knit community of fewer than 2,000, many of whom are descended from the original settlers. Brackers, as they are known, were traditionally a seafaring people who relied on maritime industries such as turtling, merchant shipping, and wrecking for their livelihood. The distinctive Caymanian catboat was invented on Cayman Brac, as was an innovative style of turtle net. After World War Two, many Brac men shipped out on bulk carriers, traveling the world’s sea lanes as sailors, ship’s engineers, pilots, and even captains. Offshore ship-to-ship oil transfer operations brought much-needed income to the Sister Islands during the 1970s and early 1980s. Today, the principal maritime activities are sportfishing along with diving and other watersports.

Little Cayman, lying west of the Brac across five miles of open sea, is 10 miles long and one mile wide. Fringing reefs encircle the island, and its highest elevation is only 40 feet. Little Cayman was settled, at least seasonally, by English turtle fishers as early as the 1660s. Following the permanent settlement of the Sister Islands in the 1830s, Little Cayman experienced about 25 years of economic success between 1885 and 1915, when first the phosphate industry and then the coconut industry were flourishing. However, the phosphate beds were soon depleted, and a hurricane, followed by the arrival of coconut blight, killed the coconut industry. The permanent population today numbers fewer than 100, although the island is rapidly developing as a diving and offshore fishing resort destination. Little Cayman is home to rare indigenous flora and fauna, including a number of wild iguanas, and supports the largest colony of Red-footed Boobies in the Western Hemisphere.

The Sister Islands, which were settled before Grand Cayman, at least on a seasonal basis, were abandoned after Spanish privateers attacked Little Cayman in 1669. Under the Treaty of Madrid, signed in 1670, the Spanish acknowledged Britain’s sovereignty over the West Indian islands that she currently occupied, which included Jamaica and, by extension, the Cayman Islands. English settlers, some with slaves, gradually populated Grand Cayman during the early decades of the 1700s. After slaves were freed throughout the British Empire in 1834, both white and black settlers came to the Sister Islands from Grand Cayman, looking for land to farm.

The Cayman Islands were a dependency of Jamaica until 1962, when Jamaica chose to become independent from Britain. Choosing instead to maintain ties with Great Britain, the Cayman Islands retain that historical link through their current status as a British Overseas Territory.

Hover over and click a number to learn more.

1932 Storm Mass Grave*

The ’32 Storm was the most tragic event in Cayman Brac’s history. Of a total population of only 2,000, 108 Brackers lost their lives, and almost every structure was destroyed. Seeking shelter from the catastrophic winds and tidal wave, a group of people gathered in the newest house on the northwest coast, a solid structure thought to be strong enough to weather the powerful storm. After the hurricane’s eye passed, the winds shifted, demolishing the home and sweeping the ruin into the sea. All 19 people inside were drowned, decimating entire families. Stunned survivors recovered the victims and buried them together close to the former homesite at the western end of the island. Marked by a ring of stones, the grave was gradually overgrown by bush, though local people remembered its general location. In 2000, the Sister Islands Nature Tourism Project, an initiative of the District Administration, with the assistance of the National Trust, cleared away the bush, cut a trail to the mass grave, and installed a commemorative sign with the names of all those interred there. Another, smaller mass grave is nearby.

Shipbuilding & Launching Sites*

Shipbuilding was an important maritime industry on all three Cayman Islands, where most food and other goods came via the sea. On Cayman Brac, many families maintained shipyards, producing primarily distinctive schooners and small sailing craft, called catboats, that were used to pursue sea turtles as far away as Cuba and Central America. Brac builders became renowned for the quality and seaworthiness of their craft, which generally were built of local wood such as mahogany, cedar, and plopnut. Often constructed and launched from a slip along the rocky shore in front of the family home, a 70-foot schooner could be completed in nine or ten months by a crew of eight or ten men. The builders generally worked without printed plans, relying instead on small wooden half-models as a template for the ship’s lines. Slips and boat-launching coves, called barcaderes, can be seen around the shores of all three Cayman Islands.

Invention of the Caymanian Catboat*

For many years, Caymanian turtle rangers pursued hawksbill and green sea turtles from dugout canoes, which were small enough to be manoeuvred into shallow water where the turtlers set their nets and retrieved trapped turtles. In 1904, Daniel Jervis, a turtling captain from Cayman Brac, designed and built a short, wide, planked boat that was more manoeuvrable than a canoe. Brackers say this vessel, the Terror, was the first Caymanian catboat, a small craft designed especially for turtling. Terror was 14 feet long with a beam of 44 inches and was equipped with both sails and oars, making it versatile and easily handled. The style was quickly adopted by turtle rangers on all three islands. Catboats became the distinctive vessel of the Cayman Islands and were recognised throughout the western Caribbean as a symbol of Caymanian ingenuity and craftsmanship. Daniel Jervis’s Terror was lost at sea in the ’32 Storm.

Peter’s & Rebecca’s Caves*

The long, high limestone bluff of Cayman Brac is riddled with fissures and caves that have long provided refuge for island residents during severe storms. Called “hurricane caves,” several of the caverns are named for people who sought shelter there during violent hurricanes. Peter’s Cave, on the northeastern side of the Bluff, is one of the largest and can accommodate more than 100 people. Rebecca’s Cave, located on a cross-island footpath over the western end of the Bluff, was used by several families during the devastating 1932 Storm. The cave is named for one family’s infant daughter, Rebecca, who, sadly, died of exposure after her family managed to reach shelter. Her little grave still can be seen in the cave.

Cayman Brac Lighthouse*

The high limestone bluff at the east end of Cayman Brac rises 140 feet above the Caribbean Sea and is the highest point in the Cayman Islands. The Bluff was selected as the perfect location for a lighthouse to guide mariners home and to warn passing ships of the dangers of the crashing surf and rocks below. The lighthouse wasn’t always successful, however, and many shipwrecks lie at the base of the cliff. The first proper lighthouse on Cayman Brac was placed on top of the bluff in the early 1900s. Brackers carried the sand needed to build the foundations up the Bluff in thatch baskets.

Columbus Sights the Sister Islands

A journal from Christopher Columbus’s fourth and final voyage to the New World gives us the first description of the Cayman Islands. Ferdinand Columbus, the explorer’s 14-year-old son, wrote in 1503:

…Wednesday, May 10th, we sighted two very small low islands full of turtles (as was all the sea thereabout, so that it seemed to be full of little rocks); that is why these islands are called Las Tortugas [The Turtles].

This description and the recorded location indicate that the islands, first feared as navigational hazards, must have been Cayman Brac and Little Cayman. Travelling from Panama, Columbus’s caravels La Capitana and Santiago de Palos had been blown far off course and were leaking badly from shipworm. Columbus was attempting to reach safety in Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) on the island of Hispaniola, but instead was forced to run his ships aground in Jamaica. The islands Columbus called Las Tortugas soon became known as Las Caymanas after the caymans, or crocodiles, that were then present. Later mariners exploited the area’s numerous sea turtles as a source of fresh meat, a practice that eventually led to the development of a turtle fishing industry in the Cayman Islands.

Prince Frederick

The Norwegian-registered merchant vessel Prince Frederick wrecked on the southern reefs of Cayman Brac in 1897. The full-rigged ship, built in New Brunswick, Canada, in 1874, was sailing from Brazil to Mississippi when she ran aground. Though she carried only ballast, she still proved to be a prize. Salvaging goods from wrecked vessels, termed “wrecking”, was an important part of life for the residents of the Cayman Islands. They salvaged necessary commodities, as well as rare luxuries, from ships that regularly wrecked on the treacherous reefs of the Islands. Nothing was wasted; even the Prince Frederick’s ballast stones were used in construction on Grand Cayman. One surprised wrecker, attempting to chop down the mast, discovered it was made of iron when his axe rebounded and sparks flew. The remains of Prince Frederick’s iron hull now lie among the coral, a lure for divers and snorkelers. Visitors should remember that all shipwrecks are protected under Caymanian law as part of our irreplaceable maritime heritage.

Soto Trader

The ghostly wreck of the island transport vessel Soto Trader sits upright in 60 feet of water off the southwest coast of Little Cayman. The steel vessel, built during World War Two, was acquired by a Caymanian firm and used as an inter-island freighter. On 2 April 1976, Soto Trader sailed from Grand Cayman loaded with goods, including propane and gasoline, for Cayman Brac and Little Cayman. On 4 April, the freighter arrived at Little Cayman and began to dispense gasoline from the ship to drums on a barge. Fumes collected in the hold; a spark ignited the fumes, and flames instantly engulfed the vessel. While most of the crew quickly escaped the burning ship, tragically, two men were badly burned and later lost their lives. The fire continued throughout the night; when morning arrived the ship sank at her mooring. The wreck, with her cargo of cement mixers and trucks, is a popular dive site today.

Privateer Manuel Rivero Pardal*

Spanish privateers rained terror and destruction on Little Cayman during the Cayman Islands’ first recorded battle in 1669. The Spanish government, angered by the English pirate Henry Morgan’s sacking of Porto Bello in 1668, issued a reprisal commission to the privateer Manuel Rivero Pardal to retaliate by attacking English holdings in the Caribbean. Instead of taking on Morgan, he attacked the small English turtling village at Little Cayman where the Jamaican ship Hopewell, along with several other turtling vessels, was anchored. Flying the English flag and sailing unchallenged within sight of the village, Rivero Pardal’s five ships opened fire and hoisted the Spanish colours. That night, 200 privateers came ashore and burned houses, took prisoners, captured the Hopewell, and destroyed several turtling sloops. Rivero Pardal composed a poem extolling his feats and tacked it to a tree at Point Negril in Jamaica as a challenge to Morgan but was killed soon after. An archaeological survey in 1979 discovered the remains of one of the English vessels, including burned ship timbers, turtle bones, muskets, and charred artifacts dating to the 17th century. Perhaps this true incident gave rise to the legend of a pirate attack at Bloody Bay.

Maritime Place Names

Several locations in the Cayman Islands illustrate the maritime origin of place names. The small island and nearby community at Little Cayman’s South Hole Sound are examples. In 1831, the British Navy conducted the first official hydrographic survey of the Sister Islands. Aboard HMS Blossom, surveyor Richard Owen mapped Little Cayman with all its coves and bays and produced an official Admiralty chart complete with water depths, marked channels, and identified reefs. Few names, however, appear on the document. This changed with the issue of the 1882 Admiralty chart of the Cayman Islands, inscribed with names honouring the first survey. In all likelihood, Owen Island was named for the first surveyor, while Blossom Village was named for his ship. Sparrowhawk Hill, on the north side of Little Cayman, is probably named for HMS Sparrowhawk, the vessel engaged in the 1882 hydrographic survey.

San Miguel

When the Spanish brigantine San Miguel plowed into the reefs of Little Cayman in October 1730, the waters claimed all but four of her crew. Sailing from Cádiz, Spain, to Veracruz in Mexico when she wrecked, the ship was part of the New Spain flota, the annual fleet that transported foodstuffs and merchandise from Spain to her colonies and returned with New World treasures. Documents from Spain and England record that she was loaded with fresh fruit for the fleet, as well as hundreds of barrels of brandy and wine. The English pirate Neal Walker was first on the scene of the wreck. He plundered the vessel’s cargo, riling the rightful Spanish owners and the English authorities in Jamaica. Remains of the brigantine include ballast stones, cannons, and anchors. As are all historic shipwrecks in the Cayman Islands, San Miguel is protected under law as part of our maritime heritage.

Rosita/Rosetta

A shipwreck off the south coast of Little Cayman poses a maritime mystery. The wreck may be the Norwegian bark Rosita, built in 1875. A composite-built ship with iron framing and wooden hull, she was lost in the Cayman Islands during an 1897 voyage to Mexico. Another theory is that the wreck is an Irish-built ship called Rosetta that wrecked in 1867 while bound for South America. Interestingly, Little Cayman inhabitants call the shallow reef at the wreck site Rosetta Flats. Ship remains, located in an area of occasional strong currents, include iron frames, windlass assembly, rigging, anchors, and a large mound of anchor chain. Further historical and archaeological research will help solve the mystery of this shipwreck. Removing artifacts from any wreck site is prohibited under Caymanian law.

Historic Anchorage

A historic anchorage is located off the north coast of Little Cayman near Bloody Bay and Jackson’s Point. The bay, one of the safest areas to anchor on the leeward side of the island, provides protection from prevailing winds, deep water close to shore, and a fresh-water source nearby. The anchorage is a small, sandy bowl with good holding ground. It is, however, surrounded by reef. Unlucky captains caught in a storm could easily find their anchors hopelessly fouled in the crevices of the reef, forcing them to cut their lines and leave their anchors behind. At least 12 anchors are imbedded in the sea bottom surrounding the anchorage. The anchors range in age from colonial wooden-stocked anchors, to British Admiralty issue, to iron-stocked schooner tackle. This area is protected as part of the Cayman Islands Marine Park system.

Maggie E. Gray

Turtling wasn’t the only maritime industry practised in the Cayman Islands. During the late 1800s, phosphate mining became profitable for all three islands. Mined from deposits of decomposed bird droppings, phosphate was a valuable component of fertilizer. In 1885, the Carib Guano Company opened a rich mine on Little Cayman. Phosphate was transferred by mule cart to the western shore at Salt Rocks, where it was loaded onto ships for transport overseas. The Baltimore schooner Maggie E. Gray, built in 1867, was engaged in phosphate shipping when she wrecked off Little Cayman in 1892. She may have been anchored to receive a load of phosphate when the wind changed direction, causing the schooner to swing at anchor and strike the shore. The vessel’s anchor and rigging still are visible among the coral heads of the reef. The remains of mule pens and the small tramway that was used to move phosphate are visible on shore.

Photo Credits

1: Martin Keeley

2, 3: Cayman Islands National Archive

4&8a, 5b, 11, 15: Peggy Leshikar-Denton

4&8b: Della Scott-Ireton

5a: Justin Uzzell

6b &14: Library of Congress

9, 12, 13: KC Smith

7&16: KC Smith & Roger C Smith.

10: The National Archives, Kew, London.

The Cayman Islands Maritime Heritage Trail Partners wish to thank the following: Ministry of Education, Human Resources and Culture and Ministry of Tourism, Environment, Development and Commerce for financial support; Sister Islands District Administration and its Sister Islands Nature Tourism Project for assistance in Cayman Brac and Little Cayman; Cayman Airways and Island Air for travel assistance; Department of Planning for sign-placement permissions; Public Works Department for sign installation; Department of Lands & Survey for maps; Designcraft for logo and sign production; Thompson Shipping for freight; Cayman Free Press for brochure design; Claudette Upton for copy editing; Peggy Leshikar-Denton and Della Scott-Ireton for project conception and coordination; the Florida Division of Historical Resources for the model of the Florida Maritime Heritage Trail; adjacent landowners and the people of the Cayman Islands for their support.

©2003 Cayman Islands Maritime Heritage Trail Partners. All rights reserved.